If you are looking for some new sources of inspiration, we’d like to introduce you to some distinctive artists, designers, and illustrators—both past and present—that we think ‘you should know.’ Some may be lesser known while others may seem vaguely familiar, either way you will discover unique talents that might just influence your next project.

In 1847, nineteen-year-old Esther Howland received an elaborate Valentine’s Day card from England. The recent graduate of Mount Holyoke Women’s Seminary was living with her family at the time and working with her father’s business—the largest book and stationery store in Worcester, Massachusetts. That Valentine’s Day card, sent from one of her father’s business associates, would forever change Esther’s life—transforming her into an industry innovator and pioneering businesswoman.1

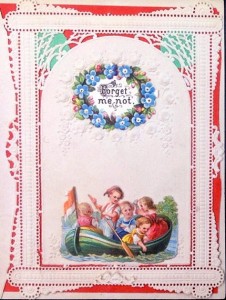

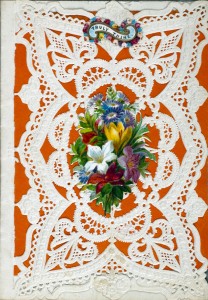

During the early Victorian Age, Valentine’s cards were generally high-dollar imports from Europe. With ornate paper lace, ribbons and floral trim, the costly cards were not affordable to the average U.S. citizen. As a result, resourceful and creative Americans would send their Valentine’s Day greetings in the form of hand-written notes or poems exchanged in secret.2

After receiving her European Valentine’s Day card, Esther Howland decided to try making some for herself. With her father’s financial support and business connections, she imported the necessary supplies from overseas. She developed a dozen original design samples and gave them to her brother, a traveling salesman with the family business. Her hope was to sell a few hundred dollars worth of cards but her brother returned from his trip with over $5,000 in orders—and so a business was born.3

To fill all of the orders, Esther reached out to her circle of friends for assistance. With approval from her family, she converted a guest bedroom into her first workspace.4 She developed a system for copying her handmade designs—whereby an employee would be responsible for just one or two elements on a given card before passing it along to the next worker. Esther would be waiting at the end of the line to ensure the quality of the finished piece. This innovative production method was an early example of the American assembly line but, in this case, staffed with an all-female workforce.3

In addition to the assembly line, she also employed women who needed to work from home. She would prepare boxes of supplies with the accompanying design template and courier them out to ladies’ homes around Worcester. After a week, a driver would pick up the finished cards and return them to Esther’s workshop for her final inspection.3

Esther’s innovations were not just limited to her production methods. She also set out to make her card designs unique within the marketplace. She insisted that the greeting, which was generally personal and intimate in nature, be placed inside the card instead of on the exterior card face, which was the custom of the time. She developed a three-dimension accordion effect by layering elements of lace with wafers of colored paper. She created a card-pulley design whereby if you pulled a string a bouquet of flowers would separate or open up to reveal the Valentine’s message inside. Her card designs also included hinged flaps, hidden doors, and interior envelopes to hold more secret messages, locks of hair, or even an engagement ring.3

As her business grew, she began working with card dealers outside of the family stationery store. She developed multiple product lines so more people could afford her cards—with prices starting at five cents and topping out at around $50. Her dealers were supplied with the full-range of product samples as well as booklets containing over 100 message or verse options for the card interior—allowing senders to customize their Valentine’s Day greeting.3

Other American entrepreneurs took note of Esther’s success and competition in the Valentine’s Day card business began to expand. To combat copycat Valentine makers, she began stamping the back of her cards with a signature watermark in the form of a capital “H.” This mark assured customers of the quality and authenticity of Esther Howland products.3

In 1879, Esther decided to merge her 30-year-old business with one of her competitor’s operations. Edward Taft was the son of Jotham Taft, another early innovator of the American Valentine’s Day card craze. Their new company was called the New England Valentine Company. The new business operated successfully until 1881 when it was purchased by George C. Whitney and became part of the Whitney Company.5

While Esther Howland may not have been the first American to go into the Valentine’s Day card business, she was certainly at the forefront of the burgeoning industry. Due to her many contributions to the trade, she has been given the well-deserved title of “Mother of the American Valentine.” With artistic flair and natural business acumen, she was able to create an all-female company that, at its peak in the mid-1800s, generated annual sales of over $100,000—all at a time when few women were welcomed in the business world.1

1 Bridgette. “America’s Mother of Valentines: Esther Howland.” We the People of the United States. 14 Feb. 2011. Web. 20 Jan. 2014. http://wtpotus.wordpress.com/2011/02/14/americas-mother-of-valentines-ester-howland/

2 “Esther Howland.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 18 Jan. 2014. Web. 20. Jan. 2014. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esther_Howland

3 Rosin, Nancy. “Esther Howland: Mother of the American Valentine.” Victorian Treasury: The Valentine Resource. Jun. 2001. Web. 20 Jan. 2014. http://www.victoriantreasury.com/howland.htm

4 Lydon, Susan. “Mother of the Valentine: Esther Howland, Worcester, and the American Valentine Industry.” The American Antiquarian Society Blog. 11 Feb. 2011. Web. 20 Jan. 2014.

http://pastispresent.org/2011/good-sources/“mother-of-the-valentine”-esther-howland-worcester-and-the-american-valentine-industry/

5 Gage, Joan. “Valentines in the U.S.: It All Started Here.” The Huffington Post. 14 Feb. 2014. Web. 14 Feb. 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/joan-gage/origins-of-valentines_b_4757152.html

Howland, Esther. Assorted Images of Howland Valentine’s Day Greeting Cards. The American Antiquarian Society. Web. 25 Jan. 2014. http://www.americanantiquarian.org/

Lora Davis Stocker is a freelance designer, illustrator and artist based in the Greater Triangle Area of NC. With diverse experience in print and digital environments, Lora enjoys working with clients of all types from small, mom and pop businesses to large global brands.